HomeReviews

Wot I Think: Black MesaSpit and shine, Mr. Freeman

Spit and shine, Mr. Freeman

Release:Out nowOn:WindowsFrom:SteamPrice:£15/€18/$20

What is the half-life ofHalf-Life? I would have long ago described Valve’s first-person shooter as my favourite game, but revisiting it last month in preparation forHalf-Life: Alyxmade clear how many parts of its design have aged.

EnterBlack Mesa, a fan-made remake of the original Half-Life, insideHalf-Life 2’s Source engine. Over 8 years since wefirst reviewed its earliest release, the project is now complete. It is a triumph on many levels, and in terms of scale and polish, the most impressive fan game ever made. But it remains, underneath, Half-Life - with all that that entails.

To see this content please enable targeting cookies.Manage cookie settings

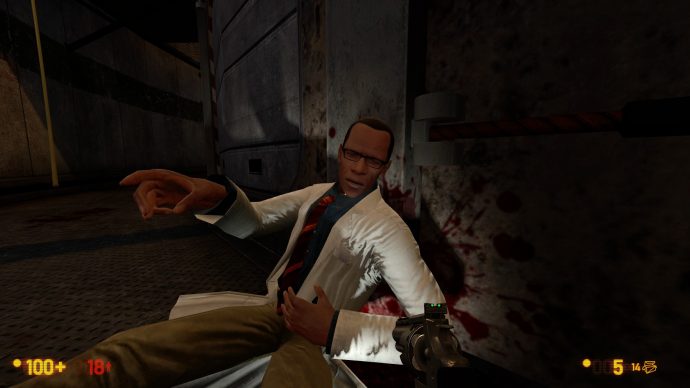

If you’ve never played Half-Life before, both it andBlack Mesacast you as Gordon Freeman, a 27-year-old scientist arriving for work at an underground research facility. You’re there to conduct an experiment, which goes wrong in typical B-movie style: portals open, alien monsters are unleashed, and the facility descends into chaos. You must fight your way back to the surface, contending with aliens and military clean-up crews, both of which are equally determined to kill you and every other scientist in the facility.

To be clear: Half-Life might have aged, but it is still a good game. Its environment design is still evocative despite its visual shortcomings, its shotgun is still fabulous at right-click-exploding enemies in satisfying showers of alien body parts, and its storytelling methods are still the template for the twenty-two years of first-person shooters that followed it. As you weave through Black Mesa’s warehouses, railways and sewage systems, fighting ninjas and flipping switches, it will become clear that the world of game design has moved on, but that Half-Life’s relatively simple horror tale holds up far better than most of its peers.

Black Mesa’s meticulous recreation does not return any of these moments to their former glory, because to do so would be impossible. You can’t see something for the first time twice. As a result, moments like the tram ride now feel overly long, even dull, as they lock you in a small box to deliver exposition and worldbuilding I’d expect a modern game to parcel out more elegantly.

What Black Mesa offers instead is a visual refresh that successfully drags 1998’s finest level design to a visual standard mostly set in stone around 2010, using a 2004 engine. It does so with grace and flair. Often, visual remasters do a terrible disservice to the original artwork of older games, jamming polygons, high-resolution textures and greebles onto every surface with little consideration for original intent. To its enormous credit, Black Mesa doesn’t do that: the spirit of each location is maintained, whether the early labs, the wood-panelled offices, or the cavernous bowels of the facility. It never feels like the level designers are using the increased fidelity available simply because they can.

When you are given something new to play with, such as the hornet hand, snarks, or crossbow, there’s an initial thrill. Even after two decades, the weapons feel weird and exciting, and the new animations for the hornet hand are particularly delightful. Such a broad arsenal of weapons is unusual these days, and I found real pleasure - relief, even - in always having a dozen death-dealing options in my pocket, rather than being limited. And yet, they’re also of limited use in most situations. I defaulted to the Magnum and the shotgun again and again, and even when a weapon was powerful, such as the gluon gun, I often avoided using it because it didn’tfeelpowerful. The gluon gun is an extremely loud and deadly hose with a substantial charge-up time, but it only causes small red splotches to appear on enemies to signify they’re being hurt - and then they simply burst.

Black Mesa retains those three things, but changes nearly everything else - and almost entirely for the better. Xen is Black Mesa’s level designers unleashed, revelling in the freedom to create something of their own. The brown islands are gone, and in their place is lush, colourful terrain. There are several gorgeous vistas to gawp at, and even distinct-feeling biomes, from alien jungles, to encroaching human outposts, to the Gonarch’s network of caves. It still feels Xen-like, and in keeping with the game’s overall style, but it’s Xen as it might have been made today. Even the jump puzzles are no longer awful - the awkward and tricky leaps between islands have been replaced with more simple traversal using a long-distance jump move. It’s properly fun.

Yet it’s not perfect, either. One of the original complaints about Xen was how divorced it felt from the rest of the game. The new Xen doesn’t have that problem - but then, I never thought that was a problem to begin with. Remember what I said before, about how Half-Life chapters often boil down to trudging back and forth to power machinery and unlock progress in a central hub? Hey-hey! That’s what Xen is about too, now, with Half-Life 2’s power cables making an appearance as you use them to wire up alien crystals to provide electricity to doors, or find ways to explode other crystals in order to flood chambers and swim up towards new corridors. After following this routine for so many hours, it feels like a slog to do it all again in Xen.

The Gonarch, meanwhile, is still more memorable for her visual design - she’s a big bollock, ain’t she - than for the actual fight. That fight takes place over multiple stages, including several segments where you’re being chased, during which the Gonarch is seemingly invulnerable to damage. It’s not any more fun for being longer. There’s still not enough visible feedback when shooting at her, either. It left me wondering whether I was missing something, and feeling as if I was making no progress until, eventually, she burst.

So, Half-Life, then. I used to say it was my favourite game of all time. Now, I’d say it’s a first-person shooter that is occasionally great, mostly good, and sometimes charmingly crap. Black Mesa smooths out most of the crap, and maintains the great and the good. It doesn’t modernise the antiquated design - but then, it wouldn’t be Half-Life if it did. As it is, it’s the best way to play Valve’s original design if you haven’t done so before, and it’s a brilliant way to retread those old ventilation shafts, if you have.