HomeFeatures

What’s the state of DRM in 2020?We don’t talk about it anymore

We don’t talk about it anymore

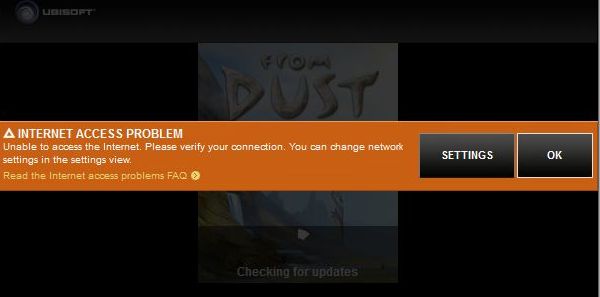

Back in the late 2000s, digital rights management - more commonly known as DRM - made itself difficult to ignore. CD copy protection programs such as SecuROM infamously limited the number of times players could install games like Bioshock on their PC, while Assassin’s Creed II required players to maintain a constant internet connection despite the fact it was a singleplayer game. At the time, this was a bit like asking people to play Assassin’s Creed II with a vase balanced on their head. Unless you’d invested in a highly stable, fibre-optic neck, at some point that vase was going to come crashing down.

Today, it’s easier for DRM to fly under the radar. Between the popularisation of digital stores and service-model games, and the fact that people today are generally a lot more online in their daily lives, anti-piracy solutions can be bound to games in a way players never notice or readily accept. But that doesn’t mean that the issues surrounding DRM have been resolved - it only means we talk about them a lot less.

The go-to example for how attitudes to DRM have changed might be Steam, Valve’s digital distribution service. WhenHalf-Life 2launched, it was the first game that required installation Steam in order to play. Without other games to buy, or many features to make the service useful, Steam was vilified in part as a draconian anti-piracy solution. These days it’s the foundation upon which much of PC gaming stands, and many of its users likely don’t think of it as DRM at all.

This leads on to the more fundamental issue with DRM, that of ownership. Back in the 90s, when you bought your latest oversized cardboard box with a game disc rattling around inside from your retailer of choice, the assumption was that you owned the box and its contents. Over time, through the advent of license agreements and CD keys, the ownership rights of players regarding individual games were gradually curtailed. DRM in particular was viewed as crossing a line because it made the limitations of ownership explicit. Not only was DRM saying “You don’t own the contents of this box,” it was saying “You can only play the contentsifyou do X, Y and Z.”

In 2020, the situation with DRM has changed, but none of the old issues have completely gone away. Faster internet connections and digital distribution may have made gaming more convenient than ever for those that have them, but having your games spread across umpteen different online accounts, all of which are hidden behind multi-factor authentication screens, isn’t exactly what I’d call convenient. In fact, there’s an argument that the shift to digital distribution is in fact a big part of the problem with DRM today. Much in the way we trade personal data to indulge our egos through social media, we trade personal ownership of products in exchange for convenient online services.

Crucially though, Valve themselves do not dictate whether a game sold on Steam requires the Steam client to launch. That’s up to the developer and/or publisher of the game in question, and there are a surprising number of games sold via the Steam store thatdon’trequire the Steam client. A full list can be seen on theSteam fandom website, but they includeCuphead,Darkest Dungeon,Disco ElysiumandDivinity: Original Sin 2. These games need to be run with an internet connection once to finalise installation, but after that the files can be moved around and the game should still launch fine.

In direct opposition to this is GOG, an online store that differentiates itself with an explicit DRM-free policy. GOG’s about page proudly displays its “You buy it, you own it” mantra. It’s interesting to look at which of the major developers and publishers have games on GOG. Ubisoft and EA both have games on there, but only those that are a decade or more old. Bethesda, on the other hand, have a surprisingly strong library of modern games available via GOG, including Dishonored 2 and Wolfenstein: The New Order.

DRM may not be discussed as much as it was 10 years ago, but as long as the industry muddies the waters between products and services, between whether players own their games or not, DRM should remain contentious. Ultimately, it’s an issue of transparency, and it will likely come to a head over the next few years as the industry gets to grips with game streaming and subscription-based models. With Netflix-style subscription services for games, like Origin Access and Xbox Game Pass, there’s no debate over ownership. It is clear users don’t own the games, but they’re also not paying £50 a go for the privilege of sort-of owning them. The question is, is handing owner game ownership in its entirety to developers and publishers the future for gaming that we want?