HomeReviewsThe Good Life

The Good Life review: tonally stupid, structurally broken, surprisingly deep and occasionally self-awareJoin the midnight cat-dog jamboree

Join the midnight cat-dog jamboree

The Good Life– which has nothing to do with the 1970s British television show about a couple ofdoom-prepping swingerswho owned an allotment in Surbiton – is a colourful open world adventure in which you play an investigative photographer charged with uncovering the secrets of an idyllic English town.

Like so many of Swery’s previous games, most notablyDeadly Premonition, The Good Life is characteristically goofy and haphazard. It can be broadly categorised as a daily life simulator — in the vein ofStardew ValleyandAnimal Crossing, but not like either of those — with a Pokémon Snap style camera mechanic in which you take photographs of interesting things and people about town for kudos and cash rewards. You can also turn into a dog or a cat whenever you like.

The Good Life Release Date Announcement Trailer (English)Watch on YouTube

The Good Life Release Date Announcement Trailer (English)

But for all of its delightful ideas The Good Life is a technical mess, and usually not an endearing one. The third-person camera swings drunkenly around above your character’s head like an attacking seagull. Naomi maneuvers like a barge. The cute, low-poly art style seen in the early trailers has come out looking all sickly and rotten, rigidly animated and lacking in any detail or lighting effects.

You can catch a cold, or hurt your back, or break a tooth, which happens seemingly at random and drags on your stamina until you bother to scavenge the ingredients required to make the appropriate medicine. Most conversations aren’t voiced, but instead each character has three or four stock phrases they’ll loudly bleatway too often, a form of aural torture not yet known to the Geneva convention.

There are also some pretty fundamental quest management issues. Only a single job can be active at any given time, effectively rendering all other quests invisible in the world. So if during one quest you accidentally stumble across a character or an item that’s important for something else you’d agreed to do, you’ll miss it completely.

And because you’re free to choose the order in which you take on the three main story threads, the major plot events of each one aren’t mentioned in subsequent chapters. The collective amnesia that repeatedly descends at the close of each act creates a haunting atmosphere of quiet, complicit malice that’s far more unsettling than the town’s monthly transformation into a midnight cat-dog jamboree.

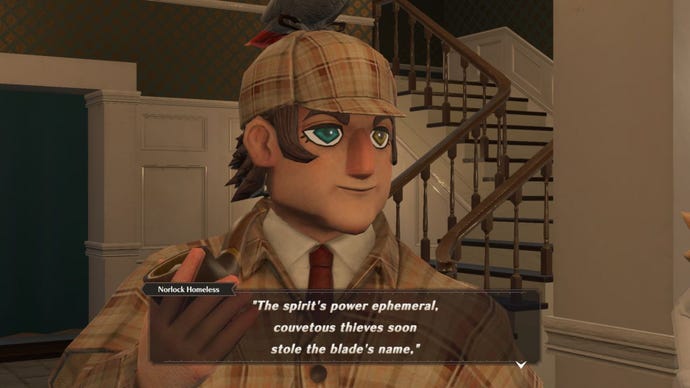

At least The Good Life has a consistently weird tone. Every interaction between characters comprises a sputtering rally of barely comprehensible sentences, careering wildly between important plot points, bafflingly asides, toilet humour, internet references circa 2018, and sometimes just plain old screaming.

Naomi has only one emotional gear: a kind of petulant, exasperated rage that gradually chips away at your own psyche until you feel weak and disarmed, like an exhausted fish on the end of a line, and when that moment comes and you stop trying to make sense of it, The Good Life drags you into its distorted clown-world and offers you comfort.