HomeFeatures

How The Impossible Bottle makes text adventuring accessibleExamine article

Examine article

Joint winner ofIF Complast year was a text adventure game called The Impossible Bottle.You should try it!It’s free and works in your browser, and you play as Emma, a little girl who has to tidy up her house and help her parents before guests come over for lunch. At least that’s how it starts, because The Impossible Bottlegoes places, and the way it goes to those places is very clever, with several revelations and a central gimmick which I’ll do my best not to spoil here. But one of its cleverest features is evident from the start: hyperlinks.

Anyone even slightly clued into interactive fiction would rightly point out that hyperlinks are hardly new to the form. Twine is built on them: they create its choice-based branching pathways. But The Impossible Bottle’s hyperlinks are different, because they don’t take you to new pages. They instead form an interface to a classic text adventure, the kind of game where you typego northanddownto explore a world, and issue commands likepick up flashlightto interact with it.

“The text game interface has a beauty, but it’s also terrifying,” The Impossible Bottle’s writer, Linus Akesson, tells me as we discuss the forbidding and inscrutable blinking prompt that has waited for your next command since the first text adventure, Colossal Cave Adventure, was written in 1976. “It’s the same terror as the writer gets from a blank sheet of paper: it can do anything, so do what?”

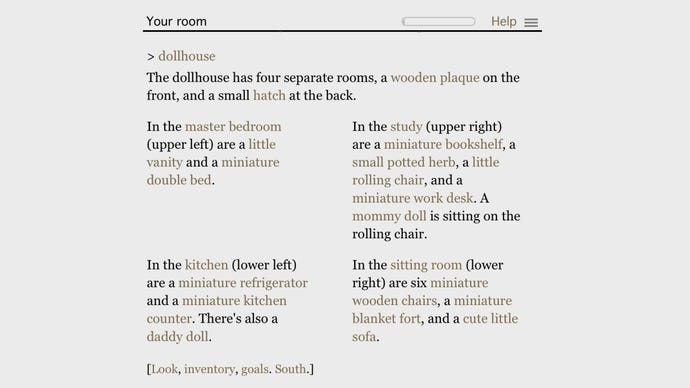

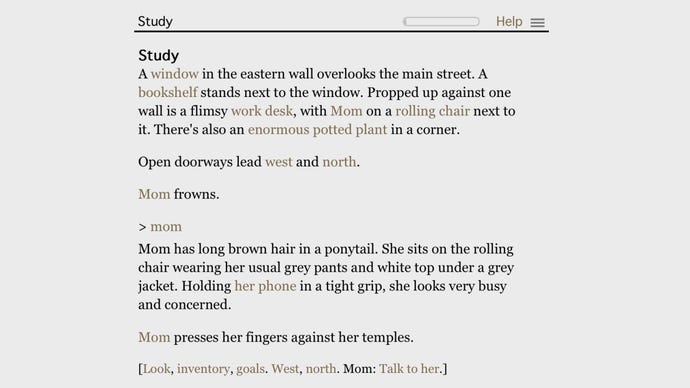

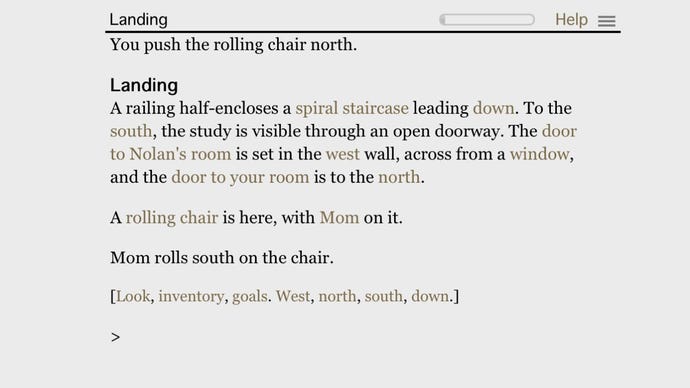

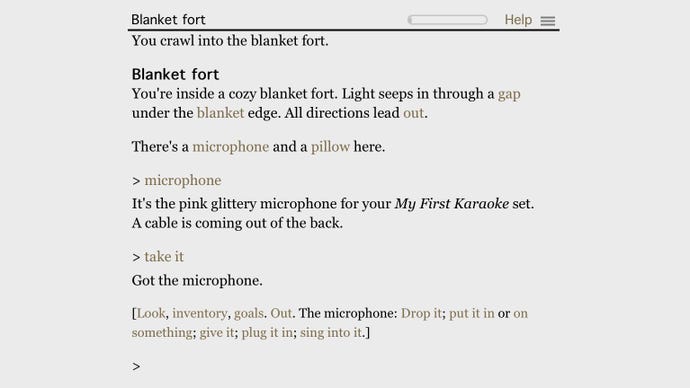

What’s surprising and exciting about using hyperlinks is that they make a text adventure easy to play. For one thing, you can play on a phone, tapping the wordeastin a room’s description to go into the kitchen. But it’s the way that they make your options clear that makes them stand out. Clicklookand the game will tell you what’s in the room; tap ontoy chestand you’ll see its description, and then below that it’ll show a contextual list of all the things you can do with the toy chest, such asopen it.

And yet Akesson loves the prompt. As an experienced text adventure player, he knows exactly what to do with it, typinglto look around andxto examine specific things, a standard series of commands that help to map out the text world. For seasoned players, the prompt is powerful, fast and flexible, so he didn’t want to jettison it, especially for The Impossible Bottle, which soon starts to ask you to perform complex tasks, placing objects inside others; retracting this; switching on that. So you can type commands and even entirely disable the hyperlinks, if you like.

“If you have an interface you think is good but is terrifying to the player, you shouldn’t hide it or take it away, you should teach it to the player,” he says. “The hyperlinks are doing that because they’re not directly controlling the game world, they’re controlling what you type at the prompt. They take you through it, and then you can do it yourself later.”

To me, a bad text adventure player, the hyperlink interface opens up The Impossible Bottle’s complexities and makes them approachable. I don’t need to try to keep Emma’s house in my head, because the game happily indicates everything around me that I can interact with, and I don’t have to remember the precise syntax the game needs to do the things I want, because it always lists the options.

In many ways I think The Impossible Bottle’s interface shares the connection between gaze and action you have in third- and first-person games: the way you interact with the things in the world that you look at. In The Impossible Bottle, you see the names of all the things around you, and then you can pick one and do something with it. It feels natural.

Akesson wrote The Impossible Bottle in a language of his own invention calledDialog. He’s not a professional game developer – few interactive fiction writers are – he’s a software engineer at the Swedish synth company Teenage Engineering, maker of theOP-1,Pocket Operators, and various other marvels of industrial design. But at night he’s into retro games as well as text adventures, and he found himself wanting to get modern text adventures running on a Commodore 64, which just can’t handle the output of languages like Inform, so he made Dialog very efficient, while also outputting to web browsers so its games are playable anywhere.

Another invisible feature is that Akesson curated the list of available actions to avoid making the game too easy, or suggesting nonsensical or inappropriate things. In the bathroom there’s a toilet, but though the game responds when you typeuse toilet, the option isn’t listed because it’s pointless.

There’sonepuzzle, though, where the key action is never listed. To describe it would be to blow one of the best reveals in the game – suffice it to say that it makes sense that it’s never shown as a hyperlink. To solve it, you have to type the relevant command at the prompt.

“People might disagree that it works but I think it does, because you’re controlling what goes into the prompt and it’s interpreted differently with the context, and that can be excused because you’re co-writing a story with the computer. But I guess I’m on thin ice from an interface design point of view.”