HomeFeaturesPsychonauts 2

How Psychonauts 2 turns the mind inside outIt’s all in your head?

It’s all in your head?

Image credit:Xbox Game Studios

Image credit:Xbox Game Studios

“It’s all in your head.” It’s a response that encapsulates all the condescension and ignorance surrounding mental health issues. And yet, in a way, it’s true. Subjective experience is an objective reality – that just so happens to be located and locked away in your head.

These individual realities can only be conveyed through language and other subjective means of communication, and more and more games are grasping this fact, turning inward to explore and map the inland empires of the mind. They have all the tools of the medium at their disposal to turn the invisible workings of the mind into landscapes of audio-visual and mechanical metaphors that can be explored and interacted with. At their best, they convey the dynamic and complex mechanisms of the psyche in a way that only this medium can.

Psychonauts 2 Review | A More Mature Story With Incredible, Zany EnvironmentsWatch on YouTube

Psychonauts 2 Review | A More Mature Story With Incredible, Zany Environments

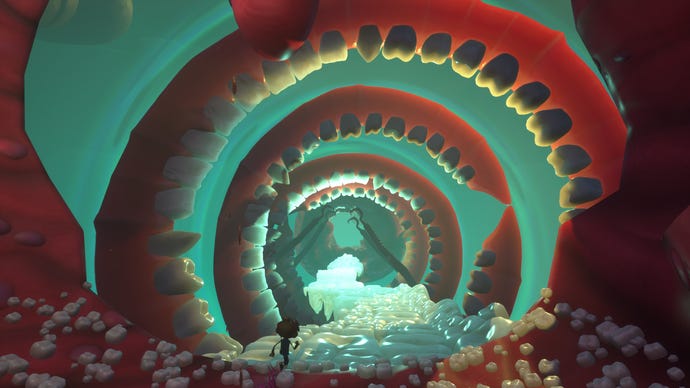

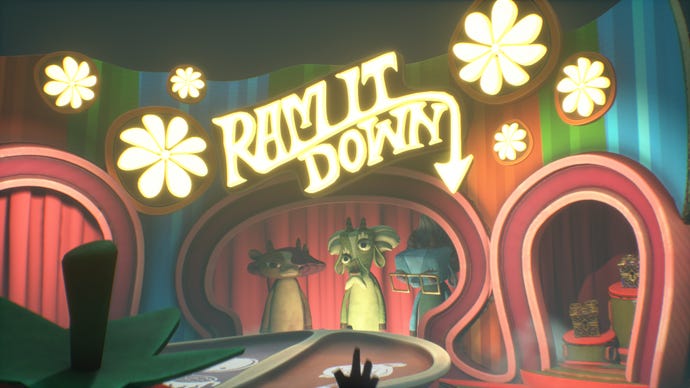

InPsychonauts 2, we follow the young psychic agent/intern Raz on his excursions into the human mind. Using a Psycho-Portal which can be attached to a subject’s head, Raz projects himself into the confused unconsciousness of colleagues, mentors, and antagonists. Each mind we explore is a whimsical yet chaotic and treacherous stage on which mental processes are being played out. They are intricate, self-contained platforming worlds full of secrets and idiosyncrasies to be dealt with, each with its own messy tangle of free associations, symbols, and metaphors that express the preoccupations and struggles of a mind.

Our goal is (usually) therapeutic; using all the tools of platforming games, we navigate and explore the mind to gain understanding, sort out emotional baggage, and fight off doubts, regrets, and anxiety attacks in the shape of pesky enemies.

Meanwhile, in Bob’s Bottles, botanist Bob Zanotto finds himself stranded on a lonely island in what is – presumably – an ocean of booze. Bob struggles with depression-induced loneliness and alcoholism, and his mind is a drowned world. The fluids symbolise both his disconnection from others, but also (as water) the potential to regrow the seeds of his neglected friendships.

Sailing the seas of Bob’s psyche, we discover other islands: entire regions of himself from which Bob has withdrawn. Through our exploration, we create a topography of Bob’s mind, demonstrating that his mind is a coherent whole, not an isolated fleck lost in the ocean. Once we bring back the seeds we have recovered from these distant parts, they sprout into distorted and terrifying versions of Bob’s lost husband Helmut, his mother and his nephew. Throughout the ensuing boss battle, Bob is wrapped in a protective cocoon: the end goal is not to defeat the monstrosities Helmut has created in his mind, but to break the cocoon and make Bob realise there’s nothing to be afraid of.

The action-adventureHellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, on the other hand, is an exploration of schizophrenia and trauma that relies on artful audio-visual effects to convey the perception, experiences, and inner struggles of Senua, a Pictish woman in the Viking age. In another point of contrast to Psychonauts 2,Hellbladeis less about looking at mental illness, and more about looking through it. Senua hears disembodied voices all around her, perceives meaningful patterns in random constellations of objects, speaks to phantoms of her dead lover and suffers through dreadful visions of death, decay, and demonic assailants. Presenting the world through the eyes of a person suffering from schizophrenia, Hellblade makes no distinction whatsoever between an objective outward realm and a subjective inward realm: everything Senua experiences is, as far as we are concerned, equally real.

Psychonauts 2, Disco Elysium and Hellblade differ wildly, ranging from whimsical comedy to psychological horror, from platformer to CRPG. And yet, they all reach deep into the toolboxes available to their respective genre to turn the mind inside out, letting it spill out into the open. In a world that still all too often dismisses mental illness as something less than real, and working from within an often literal-minded and materialistic medium, games like Psychonauts 2 do something important. They bring together empathy and wild imagination to throw a metaphorical light into metaphorical dark corners. Sometimes, you need to make stuff up to get at something real.