HomeFeaturesDeathtrap Dungeon: The Interactive Video Adventure

Deathtrap Dungeon is the museum of 80s trad fantasy you didn’t know you neededLightest dungeon.

Lightest dungeon.

OK, time for a classic palaeontology opener metaphor, I’m afraid. You ever heard of a ‘living fossil’? It’s not an enemy fromDeathtrap Dungeon, alas, but an organism that’s remained virtually unchanged for huge stretches of time. The archetypal living fossil is thecoelacanth, a fish that first appeared in the fossil record getting on for half a billion years ago, with thick, stumpy fins poised right on the cusp of becoming rubbish legs. However, it never took after its taxonomic cousins and invaded the land - instead, it persisted with that same liminal body plan, in the evolutionary equivalent of being forever on the brink of sneezing, until it got binned with the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. And then, off the coast of South Africa in 1938, a fisherman caught one. Unchanged. To look at a coelacanth is to look into deep time, and even though it’s not much cop as an actual fish, it’s beyond fascinating as a piece of living history.

So Deathtrap Dungeon, yeah? It’s that. Only it’s a game rather than a fish. And rather than providing a haunting glimpse down through the yggdrasilian roots of tetrapod biology, it’s a showcase of how simultaneously charming and rubbish 1980s trad fantasy was.

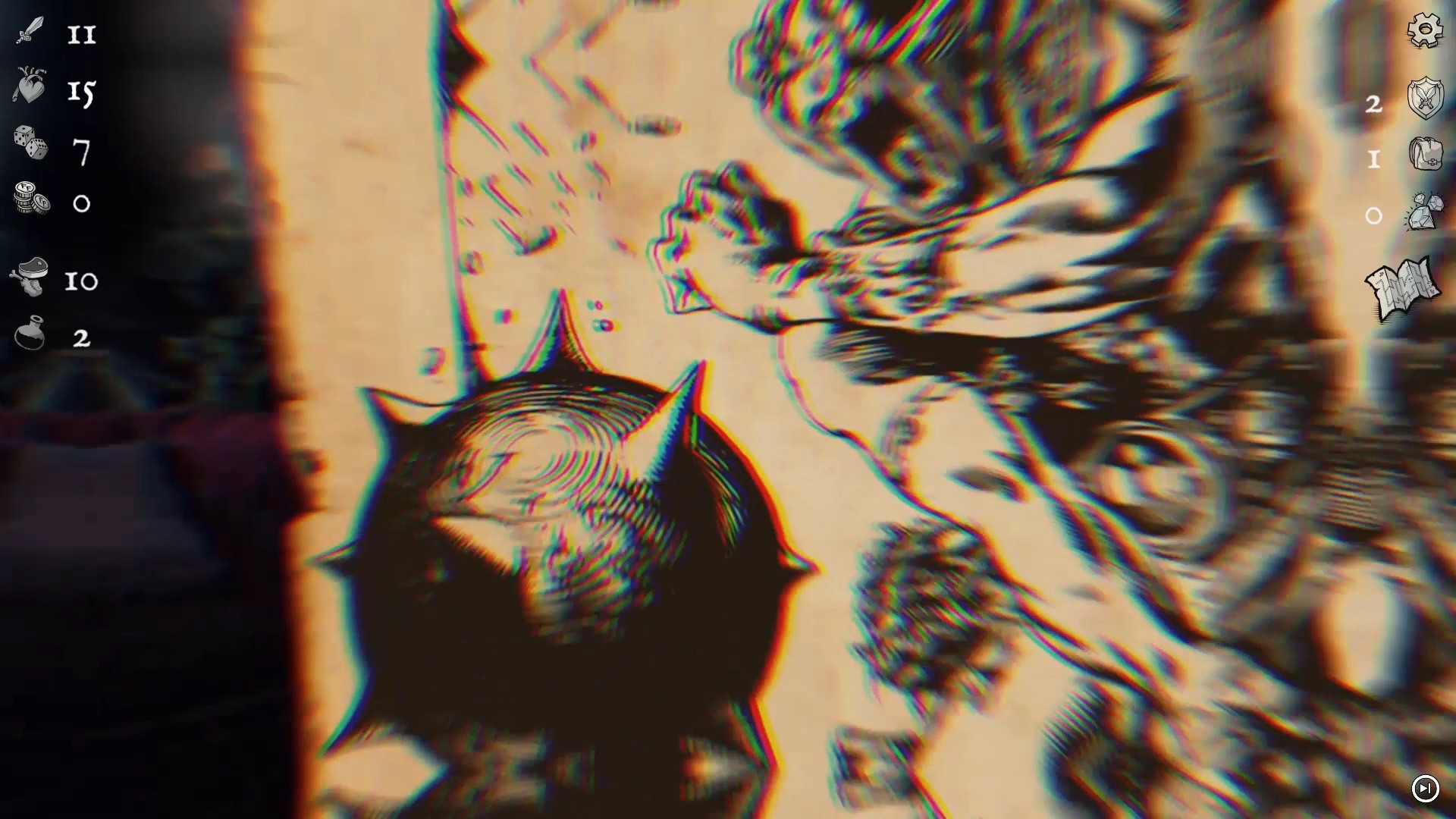

An orc! With a morning star!

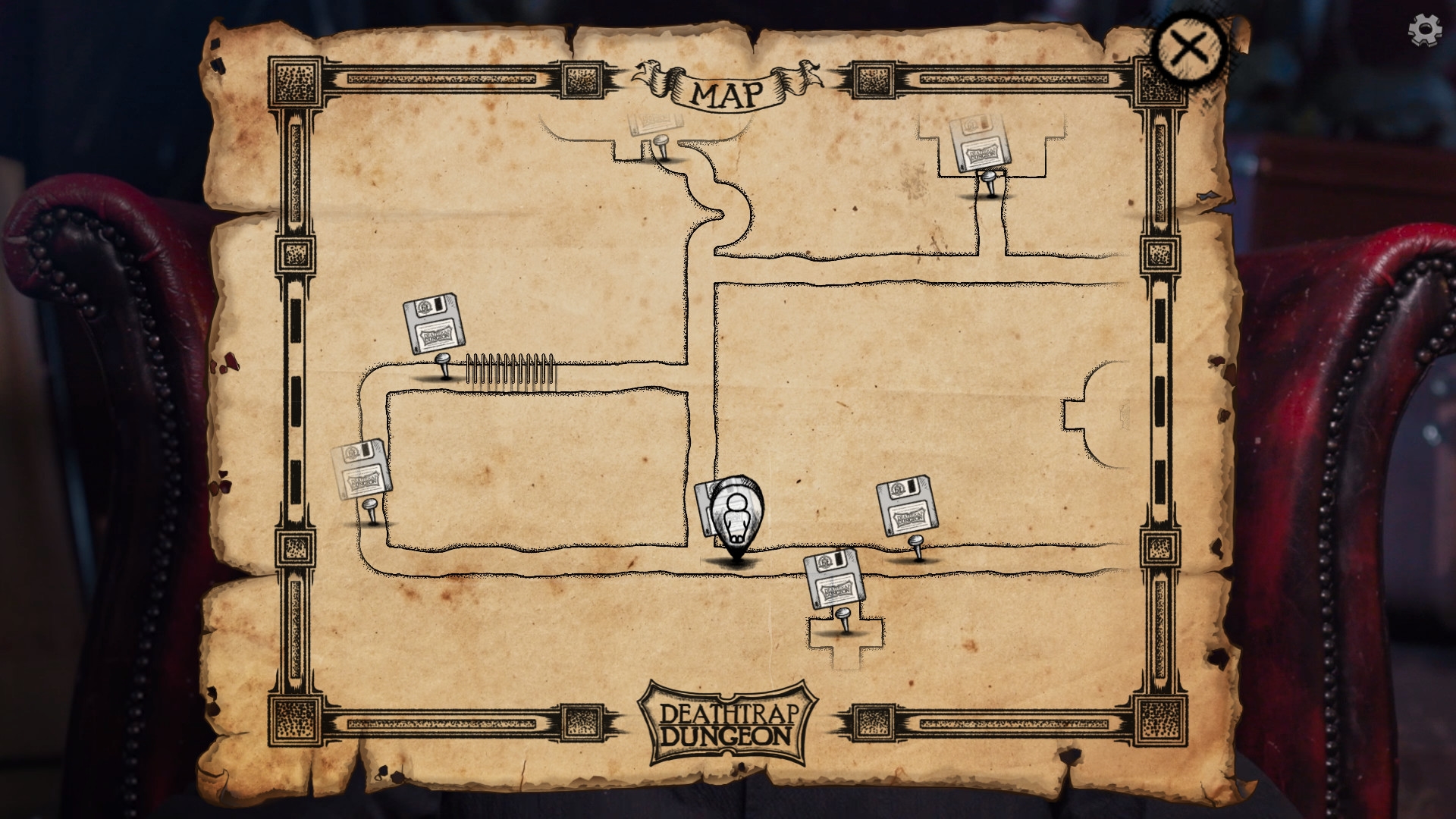

Bless, there’s even a map <3

And there’s the problem. Because when you have to actually stick to the rules, Deathtrap Dungeon is a bit rubbish. Instant death moments can occur arbitrarily at any time, with barely a narrative clue to foreshadow them, and the combat system isguff. In their one concession to modernisation, developers Branching Narrative have included an optional, streamlined version that mercifully ends each interminable stranglefest after three rounds of dice rolls, but even then it’s a clumsy, unenjoyable system. And because it would be weird to just have Eddie stare silently at you through fights, he has to constantly narrate the outcome of each blow, repeating “you sweep the creature’s legs from under it” and the like over and over, as if he’s got a peculiarly specific set of Tourette’s tics.

I love how in this screenshot, the dice look like they’re his little mates, being summoned on screen to do a little song and dance number, like the birds helping that lass clean her house in that one Disney cartoon.

I’ve got a foot in both camps mentioned above. Deathtrap Dungeon itself was published just five months before I was, but as a child of the 90s, I knew the formula. I spent hours flicking through gamebooks of various imprints, with no regard to the rule of law, as I tried to block out the sound of my nan screaming her way through the long, hideous aftermath of a stroke. As such, Deathtrap Dungeon: The Online Edutainment Experience was freighted with wistful memories for me, but it was also a chance to think critically about how fantasy has changed in the last three decades. I’ve gotten so used to modern genre fiction’s constant attempts to innovate cliché, that to experience so much unrefined generica actually felt refreshing. And weird. To encounter a barbarian who really was just a hulking, taciturn man with a sword was disconcerting when I’d forgotten that such things ever existed outside of deliberate parody. It was a relief as strange and pure as eating a half-rate fryup on a 50p plate, after years of bourbon-infused bacon and sourdough served on shovels and bits of masonry.

Any one of these options could lead to instant death. The iron plate might be made of poison. There might be an ape with a gun behind the door. The corridor might turn into a wolf.

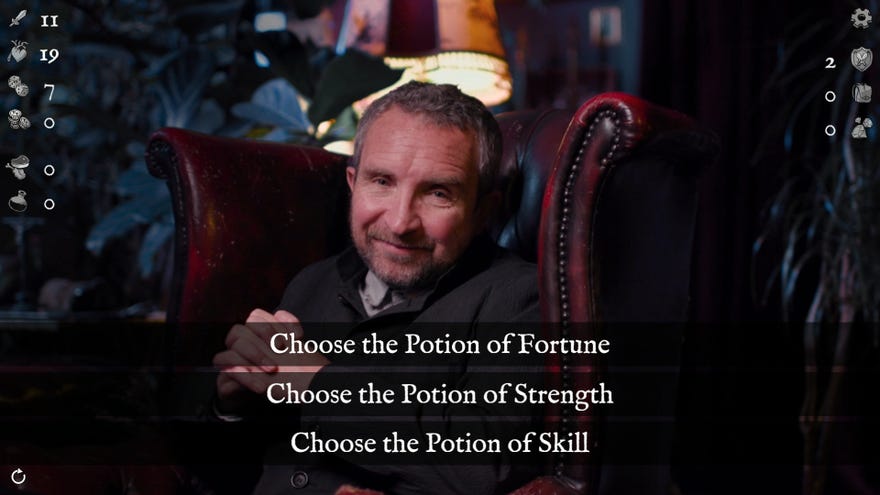

And of course there’s Marsan, who’s just lovely. Here is a man who is the very definition of a supporting actor, and I guarantee you he’s appeared in about twenty movies you’ve seen, doing solid work with characters usually just above the threshold of being named in the script. He was the science man in 2019’s sublime Statham Containment VesselHobbs & Shaw, for example, and the grim headmaster in Deadpool 2. He always does a good job. And he does a great job here. Marsan is a faintly awkward presence at first, sitting with the shy smile of a trainee vicar, in a red leather armchair so big he looks like he might get lost in it. But he’s so wholeheartedly, enthusiastically professional about every damned word of the script, that it’s impossible not to buy into it.

“Now, let’s get you a twix and then why don’t you have a nice lie down - it’s been a long day.”

And right now, with what feels like 80% of my friends running some kind of lockdown RPG campaign, it felt really good to have my own personal GM for a bit. It was face to face contact, and personal attention. And as illusory as it was, at a time like this you’ll take what you can get. It was like the social equivalent of prison wine. More than that, though, it felt like having a guide to something fascinating. Like at one of those ‘living history’ museums, where volunteer enthusiasts LARP as tudors or romans or whatever, and talk to you in character about the olden days while you look at an old engine or some geese. And there you go. Rather than being a game, Deathtrap Dungeon is a lovingly curated museum, and I think a tenner is a more than reasonable price for entry.